If you can count them, you don’t have enough.

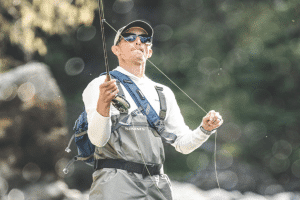

They find him. Or he finds them. If fishing lures are being transacted, if fishing lures are being debated, if fishing lures are being written about or talked about, Dan Basore is almost certain to be in the middle of the discussion.

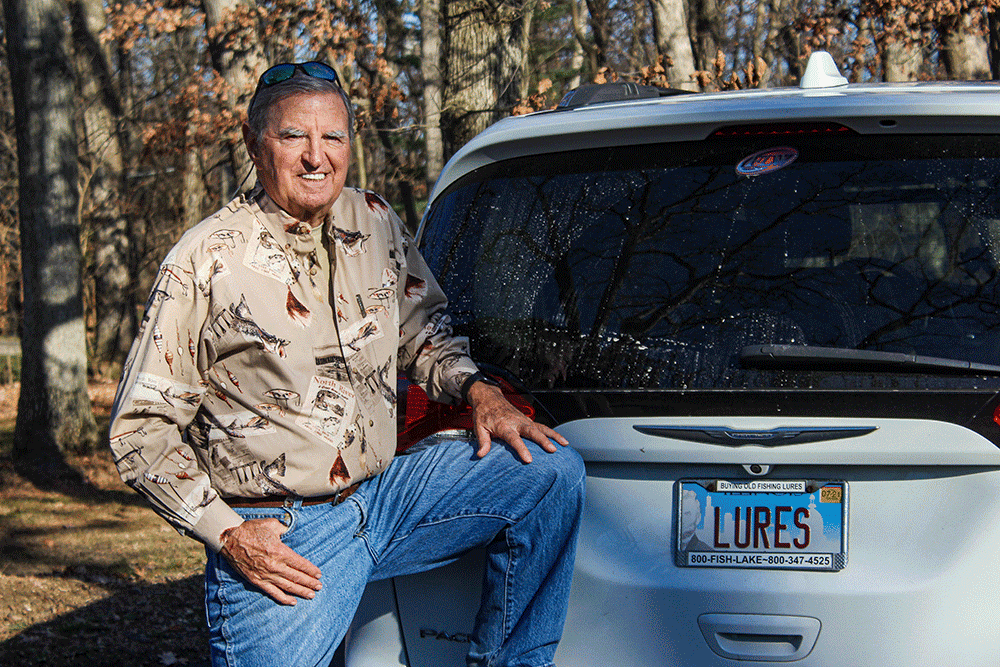

This is a man who signs his correspondence, “Lures Truly.”

He can tell you a Cleopatra fishing story, while chuckling, and marvel at hooks from 2,000 years ago that were found frozen in Alaskan glaciers.

Basore seems as if he has been around forever, but he did not actually fish with Egyptian ruler Cleopatra around 50 B.C. Supposedly, she “was showing off for Mark Antony. She had several of her servants put fish on the hooks” of her rods. “They were preserved in salt. They were already dead.” Antony got over it.

Basore does not claim possession of every lure ever wielded, nor does he claim to have seen them all, because, after all, you never know, there are ones nobody knows about that could reveal themselves any day. That hunt keeps him young and hungry, even if he is 78 and been collecting and swapping lures since he was 15 growing up in Indiana, years before moving to the Chicago area.

How many lures have passed through his hands, or live in cardboard boxes and filing cabinets, wooden carrying cases with handles, in the basement, the garage? Ten thousand? “Phooey,” Basore replies. Somewhere between a lot and infinity. “If you can count them, you don’t have enough.”

The lures are made from wood and metal, plastic, rubber, glass, springs, cloth, or feathers. Some remain in their original boxes with price tags attached, dating to the 1920s.

They have been worth 25 cents and $2,500. For 20 years, Basore has traded fishing lures coveted by others for eight different automobiles, upgrading their collections and his mode of transportation. He does not hang on to the cars indefinitely, but he does cling to the Illinois license plate “LURES.”

A one-time caddie, auto racer, car salesman, and financial services officer who retired at 57, fishing and lures have been Basore’s passion since he was a tyke. His mother, Emma Basore, who passed away last year at 99, “was my guiding light,” he says. She read him books, but he demanded to hear the one about fishing in the 1930s over and over.

Gray-haired and ruddy-faced now, Basore, at two, begged his mom to take him fishing. His three siblings had little interest in angling. The family resided near a popular bait shop by the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and he developed a rapport with owner Bill Sutphin, who made his own lures. Later, Basore inherited them.

Soon enough, Basore joined the Marion County Fish and Game Club, founded in 1907, and won his first fishing tournament by catching 64 sunfish. Basore won many more tournaments over the decades, including national casting championships.

Trophies from tournament successes are sprinkled around his home, along with rods, reels, fishing-related artwork, mounts, fishing photographs, books, scrapbooks, and oodles of lures. The house is an unofficial museum.

“It is the Smithsonian of the fishing world,” says Chauncey Niziol, a long-time friend who covers the outdoors for ESPN Radio in Chicago. “It’s not all lures, because he’s got the information. Everything.” Basore has meticulous documentation of lure history. He writes down as much as he can discover, who made a lure, when, what it cost, when it was sold. Sometimes in acquiring others’ collections, he obtains paperwork. Helen Shaw, queen of fly-tying, willed Basore her collection, and he venerates her contributions.

He was friends with Johnny Morris before he founded Bass Pro Shops and purchased one of the first B.A.S.S. lifetime memberships from founder Ray Scott.

Basore has fished in Alaska, Argentina, Costa Rica, Brazil, Mexico, Canada, France, Africa, and elsewhere, so he has first-hand experience luring in fish, from a 400-pound marlin to Arctic grayling, from tiger fish to lake trout, rainbow trout, and brown trout and the 25-pound Brazilian peacock bass hanging on a living room wall with the lure that brought its demise dangling from its mouth.

He wrote about lures and fishing for Midwest Outdoors for 35 years and brings cases of fishing lures to outdoor shows in Chicago, Milwaukee, and Indianapolis, as thousands of passers-by ooh and aah.

Strangers tell him about these marvelous, hand-carved lures he has only heard about. Basore receives letters from widows saying their husbands left hundreds of lures in the garage, and they would like to provide a new home. When examined, he may not want 90 percent of the stash. The Mrs. may insist he take all or nothing, and he takes all.

He acquired 3,347 lures from one collection. One dad’s little girl was attached to a 1940s chipmunk lure she named “Chippy.” After Basore bought it, he gave her annual visiting rights. She exercised them.

Basore is an individual clearinghouse for collectors, almost a human way-station steering gear to its meant-to-be destination. Basore is especially pleased when lures are accompanied by provenance, the story tracing the lure from inception to his custody. He enthusiastically informs the world about the little-known lure maker underappreciated in his lifetime.

Discoursing on oldies excites Basore. He mentions an 1859 minnow lure made by Riley Haskell in Ohio. The detailed trolling spoon shows eyes, fins, tail, and scales, and he considers it an historical work of art. One was once auctioned for $101,000. “It’s very rare,” Basore says. “There are 15 known to exist. The Holy Grail of old fishing lures.”

Basore used to own the lure that caught the world-record largemouth bass in Georgia in 1932. The highest price he ever heard of for any lure is $150,000, he says.

Still, after a lifetime as a lure collector, Basore is somewhat pessimistic about the hobby’s future. Mostly old-timers like him care about lures these days, he says. Young people are part of “the old is stupid culture.” Basore has willed his lures to museums and collectors who will treat them with proper reverence. “I’m a temporary caretaker of all this stuff,” he says. “I understand that.”

For decades, Basore has proselytized about fishing’s marvels and the inner world of lure collecting in lectures to adults and instructional sessions with thousands of young people, providing them with the equipment to get started and seeking to hook them on fishing for life.

Basore plans to preserve the fishing lures of the past for those future generations, but remains on a never-ending personal quest for the lure he has never met. “I want to have an open mind,” he says. “The world’s a big place.”

And there are many fish in the sea waiting to be lured in.