How the Kootenai Tribe and partners are conserving burbot in Idaho.

Only 67 members of the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho remained in 1974. With no land and most members living in desperate conditions, they tried to secure their survival with a Hail Mary: by declaring war on the United States. The peaceful war, more publicity ploy than security threat, worked. President Gerald Ford granted the Kootenai 12.5 acres around Bonners Ferry in northern Idaho—which they leveraged to gain services and improve living conditions. Since then, the tribe has grown to 300 members and the land to 2,695 acres.

Decades later, when only about 50 burbot remained in the Kootenai River, the fish could not declare war themselves. The Kootenai Tribe, which historically caught the leopard-spotted freshwater cod for food in winter, stepped in and fought for them. In 2019, the conservation plan’s success brought the burbot population to about 60,000 and allowed for recreational burbot fishing on the Kootenai River for the first time in 27 years.

Sometimes called freshwater ling or eel pout, burbot are native to the Kootenai River (and nowhere else in Idaho), and are an average of 18 to 24 inches long and weigh two to four pounds, but they can grow up to 35 inches long and weigh more than 13 pounds. Their mild flavor and firm, buttery flesh, unencumbered by bones, makes them easy to cook and a chef favorite to serve. For the Kootenai, the once abundant fish formed a significant part of their diet, especially in winter, when the fish flowed but little grew.

In other parts of the country, including the Upper Midwest, Alaska, and Montana, people fish through ice for burbot, but the Kootenai River no longer freezes, something that Kenneth Cain brings up as a factor in the initial dwindling of the population. A professor of aquaculture and fish health at the University of Idaho and the associate director of the school’s Aquaculture Research Institute, which worked with the tribe on the burbot recovery project, Cain explains that the building of the Libby Dam in 1975 fluctuated the flow and likely warmed the river at times. Combined with a commercial fishery at one point in British Columbia, climate change, and overfishing, the species dwindled.

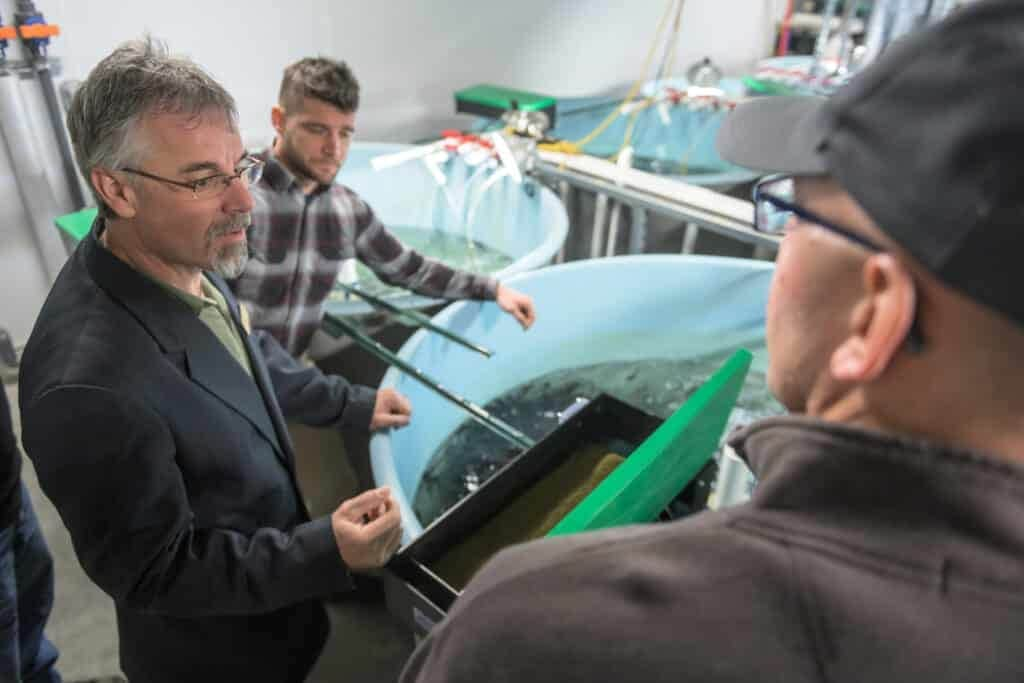

The Kootenai Tribe had already been working on recovering sturgeon populations when they tapped the University and Cain’s program to work on restocking and rebuilding the burbot population in 2003. “With this species, there hadn’t been hardly any work done on how to raise these fish in captivity,” says Cain. Because the intervention began before the species was listed as endangered, he explains, they actually had a little more flexibility in how they could restock—including allowing them to use the closest genetic match available, burbot sourced from Moray Lake in British Columbia, at the headwaters of Kootenai tributaries, to begin the project.

They brought in chillers that could keep their experiments as cold as the iced-over river during spawning season, gradually bringing the temperatures down. Thrillingly, they succeeded at getting the burbot to spawn the first year but then realized it only got more challenging. “They’re like three millimeters long when they hatch, they hatch without a mouth, and you have to feed them small plankton that you actually have to grow, as well,” describes Cain.

The first three years, Cain and his team focused on techniques that grew the fish to a size—five grams±—that not only allowed for safe reintroduction to the natural habitat, but also for tagging so they could track the fish. In 2009, they acquired the necessary permits and had grown enough fish to a large enough size to release their first fish. Each year, until 2014, the University produced fish and released them late each fall, with Idaho Fish & Game tracking them as they journeyed the river. “Survival was quite high,” says Cain, and they prepared for the next phase of the recovery.

In 2015, the Kootenai Tribe got a permit to build its own hatchery and took over the stocking. By 2019, the burbot population grew large enough to meet the Idaho Fish & Game’s criteria to reopen sportfishing and led to sport fishermen catching 500 to 700 burbot during the inaugural season.

The fish peak during the chilly weeks of February and early March and come to shallower depths only during the night. But for the unattractive fish with a reputation for tasting like lobster, 2023 now brings anglers their fourth year of reeling in Kootenai River burbot.

Cain and his team at the University have since moved on to looking at the potential for raising burbot as a commercial food product. The Kootenai Tribe, meanwhile, has developed methods for genetic tagging that allow them to stock the river using larvae, meaning the burbot get introduced much earlier to the natural environment and at a much smaller size. Next, researchers hope to use the genetic tagging to show that the recovered population is reproducing on its own in the wild. “The overall goal is to have a self-sustaining, naturally recruiting population,” explains Shawn Young, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Fish and Aquaculture Program Lead Environmental Consultant.

But even without that icing on the cake, the multitude of different groups and people that worked for almost 20 years to replenish burbot stocks in the Kootenai River show the possibilities in reducing and reversing the loss of species. Burbot return to the Kootenai River, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho can again fish for their traditional food, and local sport fishermen can again brave the frigid temperatures for the ugly but wildly delicious local freshwater cod. For the second time in 50 years, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho have shown, in the words of the tribe’s fish and wildlife director, Sue Ireland, “Extinction was just not an option.”