'Naked and Afraid' standout star Laura Zerra is a badass. The survivalist shared her journey with Hook & Barrel, and it's inspirational to the maximum.

Naked and Afraid star, Laura Zerra, was on a late-season, backcountry elk hunt on the top of a mountain in an Idaho national forest when a whiteout blizzard swept in, blinding her and skewing her sense of direction. The undulating hills made climbing down difficult, and with every step she risked plummeting into an air pocket, breaking through the snow until her armpits stopped her from suffocating. She’d crawl free, her hands too frozen to attempt a fire even if she could find a place to stop. She had no emergency beacon, but that did not matter: If she pressed the button, no one could reach her in time.

“Realizing that no one was going to save me was an amazing, beautiful, horrific moment where I knew my fate was entirely in my hands,” she says. “When I thought I had nothing left, I found a little more in the tank. I kept moving despite the sense of hopelessness in wondering if I was wasting energy by going in what might be the wrong direction. I did a manual override and said, ‘Moving is keeping me alive.’”

Laura Zerra Stares Straight at Death

Zerra has come close to death more times than she can think about: Lightning has struck next to her, she’s come face-to-face with grizzlies, swam in waters with Great White sharks, almost gotten hypothermia, and was swept away in a river.

Laura Zerra even survived five episodes of the Discovery Channel’s Naked and Afraid, a show that chronicles two survivalists—one man, one woman—who are strangers until they are dropped into a harsh wilderness where neither of them had been before with one survival item each and no food or water. Oh, and no clothes. But we’ll get to that in a minute.

Zerra is no weekend warrior; this is the way she has lived for most of her 35 years. Raised in a suburban neighborhood in Western Massachusetts, she gravitated toward the second-growth forest and abandoned tobacco fields at the end of her road.

Growing Up Wild

In her youth, she watched the wild animals, especially one pack of coyotes that tolerated her enough to let her hang close by. “The woods were where I felt most at home and most fulfilled. I would be bummed when I had to go home at night, wondering why I was this alien in the forest,” she says. “It inspired me to go on this quest to become a human animal—for a lack of a better word—and figure out how to exist in that environment.”

Zerra began wondering about things like what she could eat in the wild and how to build a better shelter. She read books, trying concepts out and learning from her failures. She realized that the glory of being a survivalist is she did not need much to live.

As early as middle school, Zerra was reading about traditional people, fascinated by how our ancestors lived and died by survival skills, how they hunted, knew the local plants and were able to make their own tools and weapons.

A Higher Education in Academia, Roadkill, & Survival

She increased her knowledge by double-majoring in Anthropology and Biology and minoring in Environmental Studies at Connecticut College. It was there she met Manuel Lizarralde, an anthropology professor who grew up with a tribe in Venezuela. He taught her how to build bows and hunt. It was a turning point for Zerra who had become a vegan in high school.

“I realized what I hated was the thought of raising an animal for slaughter. We are carnivores," she said, "We have canine teeth and are designed to eat meat as part of our diet."

It occurred to her that eating roadkill was the most sustainable thing she could do. “That was kind of horrifying to a lot of people, but the way I saw it, roadkill was local, organic, free-range, and fresher than what you get in the store,” she says.

She took a moral approach to hunting and found a spiritual aspect. “It isn’t like I enjoy the killing part, but that’s what you do when you can’t photosynthesize: You have to kill something to eat, whether plant or animal. But here’s how I think: If I take the life of an animal to further my own, I have to make my life worth it,” she says. “I use all the animal and honor it that way.”

Laura Zerra Hones Her Skills as an Outdoorswoman

Off-season, she honed her hunting skills, practicing, stalking game to see how close she could get and learning their habits. She hunts using a bow, compound bow, or rifle. In Australia, she learned persistence hunting by live-catching feral goats. “We run on two legs, don’t have hair, and sweat efficiently. We are endurance athletes designed to run down animals, which can’t cool as well,” she says. “It was amazing to know we are still capable of using our body as it was designed.”

Zerra’s survival skills are largely self-taught. She capitalizes on work opportunities to further her knowledge. This started in college, when she spent summers working at Great Hollow Wilderness School in Connecticut teaching primitive survival and interning with the Buffalo Field Campaign in West Yellowstone, Montana, where she honed her survivalist skills.

Over the years, some of her other jobs have included working as a farrier, taxidermist, on an offshore crab boat, hunting mushrooms, planting trees, leading horse treks, and processing wild game. “I’m addicted to learning new things,” she says. “It all tied into the bigger picture: the taxidermy and meat processing were so I could better take care of my own needs; the farrier skills were for if I was out on a pack trip and needed to shoe a horse.”

To further sharpen her survival game, after college Zerra bought a one-way ticket to Cancun, Mexico, with the little money she had, hitchhiked and hopped freight trains to Oaxaca, then up the west coast, studying jungle survival. “I wanted to see if I could travel without money,” she says. “I inserted myself into areas, met locals, and researched food. My motto is just jump into the fire with both feet and don’t look back.”

Zerra Goes All Out on "Naked & Afraid"

Laura Zerra was at a friend’s house on a mountain when she got a call from a casting agent to see if she would be interested in doing an episode of Naked and Afraid. “I was told I’d be dropped off somewhere with nothing and live off the land with a random stranger in a place I’d never been—and I was like ‘Sign me up!’ It’s a free adventure and totally weird,” she says. She did five episodes: on a Panama island, in the Peruvian Amazon, in Colombia, on an Alaskan glacier, and a 60-day challenge on the Philippine Island of Palawan.

While the physical part came naturally, she found the mental demands were more challenging. Her expectation was that it would be like previous survival trips. “But there were cameramen. There was a mental aspect of weirdness because they were clothed and you were not, which gives you a sense of vulnerability,” she says. “Plus, you know they’re eating when you’re starving, and you can’t talk to them since there’s this barrier.

"Think hunting is hard with one other person? Imagine how difficult it is with five well-intentioned camera guys.”

Adapting and Overcoming Adversity, On and Off Camera

A “ridiculous” memory from the show was when she and her partner, EJ Snyder, were called to film the Amazon segment. Three people had already quit the challenge since the bugs were so bad and there was not enough footage for an episode. When Zerra asked the locals how they dealt with the bugs in that area, they said, “We don’t go in that area.” Zerra and Snyder’s hack: They slept with the burlap bags the show gave them over their heads at night. “We looked like deranged scarecrows,” she says, “but the mosquitos were so thick we’d breathe them in and choke on them.”

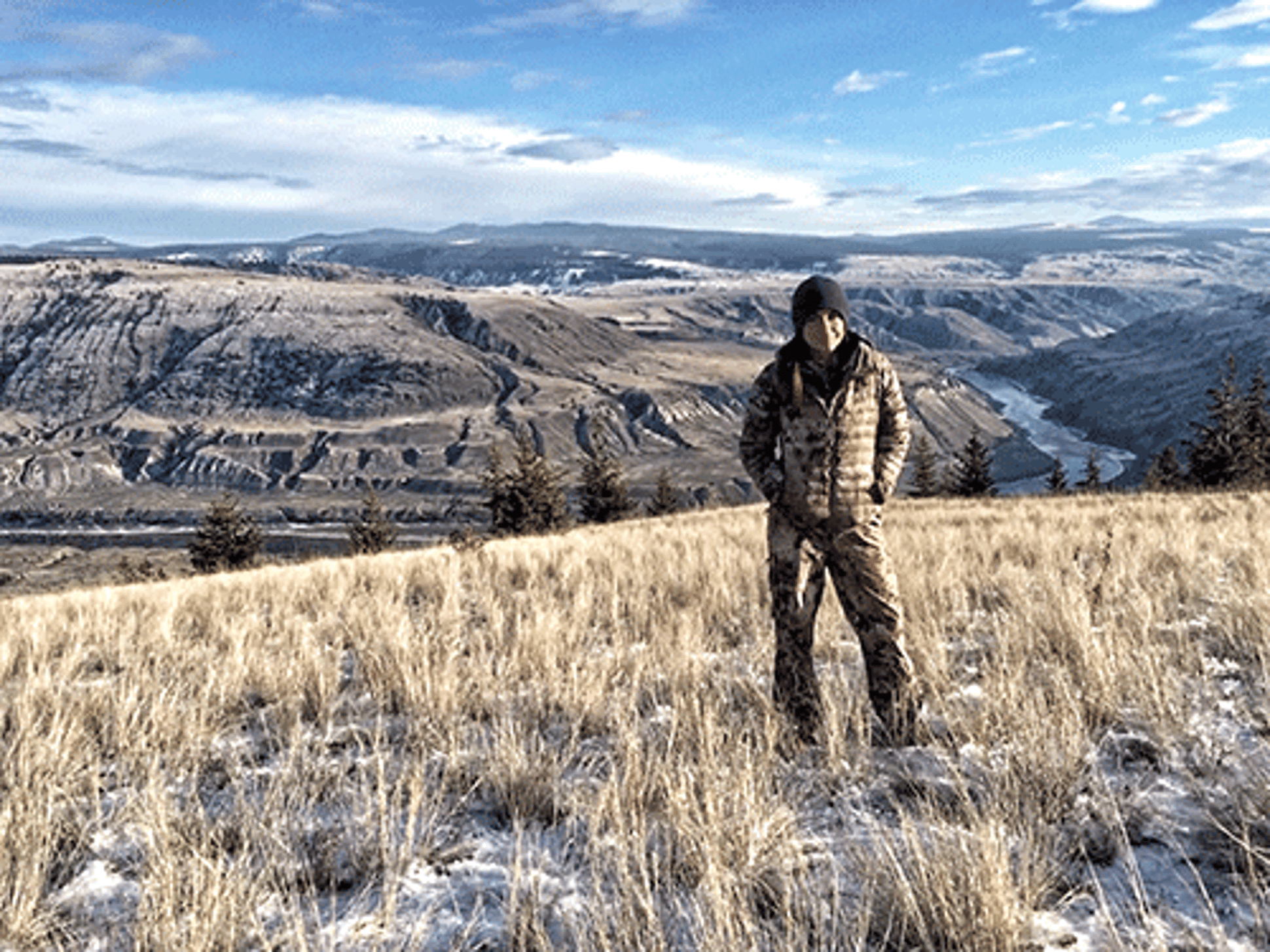

The turn of the new year found Zerra in Montana about to embark on another adventure. This begs the question: will she always be a nomad?

“Being in one place forever is a nice thought,” she says, “but my friends are scattered everywhere, and there are so many places I love in the world I just can’t stop.”

Build a Laura Zerra-Worthy Survival Kit

- A knife and lightweight scalpel blade.

- A lighter. Zerra puts it in a plastic bag to keep it dry. She wraps fabric medical tape around it, which she uses for “a million” tasks, especially covering blisters.

- Needle.

- Dental floss. Zerra says it has many uses such as cordage for traps, fishing line, and sewing.

- Fire paste or something flammable. “If you are out in the middle of a torrential downpour, and your hands are so cold you’re afraid you can’t start a fire, squirt a little bit of that on, and it’ll stay lit for a long time,” she says.

- Superglue to seal wounds.

- Paracord.

- Compass.

- Emergency blanket. “These foil blankets can make a great shelter and heat reflector if you have a fire. They are light, take up little space, and will literally save your life,” she says.

- Caffeine for energy.

- Pain reliever like Advil.

- Headlamp.

Survival Tips for Hiking and Hunting in the Woods

While flexibility and being able to improvise are some of the most important traits for survivalists, a good survival kit helps. When you are in a situation, the first thing to do is think about it logically. “You don’t want to get emotional or scared,” Zerra says. “Prioritize your most pressing need—food, fire, shelter, water. Ask: What will kill you first? It’s either dehydration or more likely exposure. Stay in the moment; do not think of hypotheticals. Look around and see what you have and how you can use it.”

Shelter building is important, she notes, but it does not need to be large or elaborate. “I build a shelter just for my body and a mini-shelter for the fire,” she says. “Small shelters take less resources, time, and energy to make.”

A Modern Guide to Knifemaking

Zerra wrote A Modern Guide to Knifemaking to create the book she wishes she had when she started making knives. “I wanted to break down the entire process in the simplest of terms and have the reader—who I assumed had no prior knowledge—be able to follow the instructions and make a knife from start to finish,” she says. The book imparts wisdom on: creating the design, making a prototype, choosing and buying steel, building a forge, making a handle and sheath, and sharpening techniques.

Folding knives are fine for everyday use, Zerra notes, but a knife made of one solid piece will not break if you’re on a wilderness adventure. “The knife just has to work; you don’t have to take it to the highest level,” she says. “Just go and do it. Don’t let money or space stop you; you don’t need a lot of either. Just make a sharp, pointy thing.”

This article was originally published in February 2021.