Click to listen to the audio version of this article.

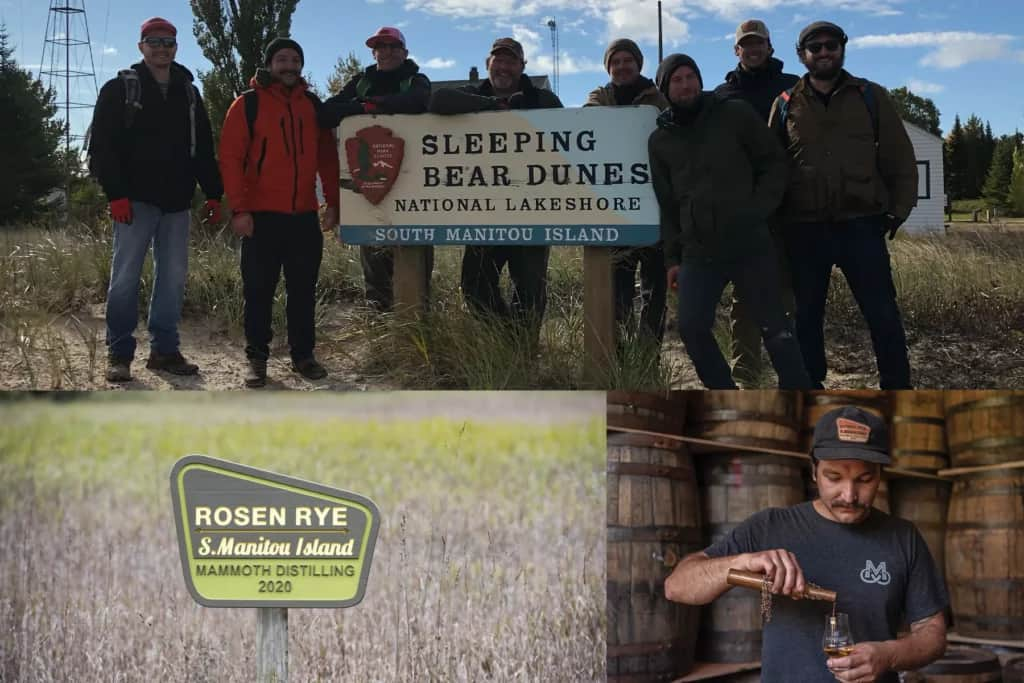

The Next Big Whiskey Thing Is Happening On Michigan’s South Manitou Island

Say “Manitou” to most sportsmen, and they likely think of the annual management deer hunt on North Manitou Island, Michigan—a weeklong special-permit affair for 200 fortunate hunters. But if you look further south, you’ll discover another Manitou doing something nearly as cool.

Where North Manitou became famous as a place filled with deer, South Manitou Island, located about eight miles south within Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, has gained a reputation for another remarkable aspect of Michigan’s ecology—grain. More specifically, Rosen Rye—once the most prized grain in America—is making a comeback thanks to a distillery in Traverse City. And if tastings from their early barrels are any indication, Rosen Rye might just be the next big thing in the world of spirits.

Behind The Grandest Grain

Rosen Rye was first introduced to America by a traveling Russian graduate student named Joseph Rosen, who brought the grain to an enterprising professor at Michigan Agricultural College, now Michigan State University. Noting its larger-than-average head and tolerance to cold weather, Professor Frank Spragg began propagating the grain all over the state.

It was an instant hit, helping Michigan become America’s leading grain-producing state in the 1910s and winning Chicago’s World Grain Expo 11 out of 12 years. It was used widely in pre-Prohibition whiskeys and bourbons, giving them a spicy, viscous profile.

The problem was that Rosen Rye became so widely planted that it soon began to suffer from cross-pollination, diminishing its genetic advantages. To preserve Rosen Rye’s purity, Spragg planted several acres on South Manitou Island in the middle of Lake Michigan. Its distance from the mainland and the prevailing westerly winds prevented birds and other elements from contaminating the stock.

Still, because Rosen Rye wasn’t as available, it gradually fell out of favor, and a century later, few remember it—not even Chad Munger and his team at Mammoth Distilling, a craft distillery operating on the waterfront in downtown Traverse City. However, one afternoon, Mammoth’s whiskey maker was doing a bit of research and discovered an old Schenley Whiskey advertisement in Vanity Fair, proudly proclaiming it was made from "the most compact and flavorful rye kernels that Mother Earth provides.” Of course, it was Rosen Rye from South Manitou Island Michigan.

“You can’t walk into a liquor store today and find a bottle that told you what grains were used in whiskey,” Munger says. “So, we thought this must be really historically relevant. But we didn’t know if this was just marketing shtick or if there was really something significant about these grains.”

Munger and his team visited South Manitou and met with park rangers to inquire about Rosen Rye. They directed him to a photo exhibit in the visitor’s center that tells the story of the long-lost grain. Eager at the prospect of reviving Rosen Rye, Munger contacted the USDA and received about 18 grams of seed from the seed bank in Utah. Michigan State cultivated it in a greenhouse until Munger had enough seed to plant around an acre. The question then became, where to plant it?

Bringing History Full Circle

“We knew it was probably going to have a cross-pollination problem if we randomly planted it like they did in the early 20th century,” Munger says. “So, we decided to close the circle and restart history. If we could get access to those original farms on South Manitou Island and turn them back into the seed farms that they were in 1920, that would be an amazing story.”

The National Park Service was surprisingly receptive to the idea, as they had preserved the old farmhouses and believed Munger’s plan aligned with their educational mission. The issue, of course, is that this was a remote island in the middle of Lake Michigan, with no power, no water, and no development.

Munger was given the task of clearing the fields and planting the grain, which was no small feat. The project required transporting a tractor to South Manitou Island, along with all the necessary fuel and a crew to restore the overgrown fields to farmland. Munger says that it cost him nearly $2,000 a trip.

“They were about 9 inches deep in poison ivy, and you had to pull it out by hand,” he says. “I put two guys in the hospital clearing those fields; it was a nightmare getting it done. There’s no help, there’s no power, it was farming the old-fashioned way, and it doesn’t actually make any money. But it’s a fantastic story, right?”

The Mammoth Difference

Mammoth’s first go at growing Rosen Rye yielded about 16 acres of grain, costing about 38 cents a pound once he factored in all the costs. It’s not profitable, at least for now. But Munger says this is only the beginning. Two years ago, Mammoth did its first 20-barrel run of Rosen Rye, and while it’s not ready to see the public yet, the industry buzz is huge.

“There’s not a single distillery east of the Mississippi who hasn’t expressed interest in going out (to South Manitou) and seeing what’s going on,” Munger says. “There’s so much bourbon being produced in Kentucky right now, there’s a bubble, right? And brands are looking for ways to differentiate. So, the industry has a real interest in using Rosen Rye as a flavoring component.”

Munger and his team have tasted the unfinished product, and he says he can already tell it will be something special.

“Even at six months (aged), we blind tested it with people and they guess it’s aged two, three years,” he says. “The first thing you notice is that very full-of-mouth feel and really full-bodied. I've never seen anything like it. Super full-bodied and spicy.”

The first batch won’t yield enough to sell outside Mammoth’s Traverse City tasting room, so whiskey connoisseurs will have to travel to the cherry capital if they want to be the first on Rosen Rye’s comeback tour. More will be coming in subsequent years, though, as Munger and company have planted 600 acres on the mainland. He’s been careful to plant it far enough away from other crops to prevent cross-pollination. The long-term goal is to bring back Rosen Rye’s state-of-origin effect so it contributes to Michigan’s agritourism economy.

“Our goal here is every time we bring a grower on board to grow Rosen Rye, we try to help them get a distilling license,” Munger says. “So now they've got a single estate whiskey to sell in addition to the grain. They get people to visit their farm, buy a bottle, buy other things they make, go for a hayride, go to a corn maze, there’s lots of opportunities for economic growth.”

For now, watch for the first release of Rosen Rye in nearly a century next year. And when you head to North Manitou Island for the big hunt in 2025, you might just have a bottle of America’s newest—and somehow also one of its oldest—whiskeys to keep you warm by the campfire.

Five Roaring 20s-Style Rye Drink Recipes

1) Manhattan

- 2 oz rye whiskey

- ½ oz sweet vermouth

- 1 dash bitters

- Cherry garnish

Put the rye, vermouth, and bitters in a cocktail shaker with ice and stir. Strain it out into a martini or rocks glass. Garnish with cherry.

2) Sazerac

- 2 oz rye whiskey

- ¼ oz absinthe or anise liqueur

- 1 sugar cube

- Peychaud’s bitters

- Lemon twist

Fill a rocks glass with ice. In a separate glass, put three dashes of Peychaud’s bitters on the sugar cube and muddle them together. Add the rye and stir. Toss the ice from the rocks glass and pour absinthe inside, swirling it around the cover of the glass. Toss the absinthe, then fill the rocks glass with the rye. Squeeze your lemon twist on top and serve.

3) Scofflaw

- 2 oz rye whiskey

- 1 oz dry vermouth

- ¼ oz lemon juice

- Grenadine

- Orange bitters

Fill a shaker with ice, rye, vermouth, lemon juice, a couple dashes of grenadine, and one dash of orange bitters. Shake well, then strain into a martini glass.

4) The Blinker

- 2 oz rye whiskey

- 1 oz grapefruit juice

- 2 tsp raspberry syrup

Shake all ingredients into a cocktail shaker and strain over a rocks

or stem glass. Garnish with raspberries (if you’re man enough).

5) Vieux Carré

- 1 oz rye whiskey

- 1 oz cognac

- 1 oz sweet vermouth

- ½ tsp Benedictine

- Angostura bitters

- Peychaud’s bitters

Put all ingredients into a cocktail shaker. Add two dashes each of Angostura and Peychaud’s bitters. Shake and strain into a rocks glass and garnish with a lemon twist.