Modern gamers who like to camp and play the sniper role often brag about "one shot, one kill," as do plenty of keyboard sniper aficionados but during the American Revolution, it wasn't a game. The muzzle-loading firearms of the era fired just one shot, and at best, a well-trained soldier of the era could fire three to four rounds per minute.

The smoothbore muskets also had an effective range of just 50 to 100 yards. Making a "kill" was as much about luck as skill. But while larger, organized militaries still relied on massed volley fire rather than precision, newer firearms and the skilled hunters in the New World for whom missing a shot meant going hungry gave rise to the first sharpshooters during the American Revolution.

Lined Up

The real power of weapons like the British Land Pattern Musket, also known as the "Brown Bess," and other smoothbore muskets were designed for massed, short-range volley fire at relatively close range.

This "line infantry" emerged in Europe more than a century before the Revolutionary War to maximize firepower against the enemy. Ironically, the same massing of troops made it likely that the other side would also score a number of hits. Yet, this practice continued into the early 19th century, even though the tactics were outpaced by weapon technology.

The Continental Army and American militia units also employed line infantry tactics, but the war also marked by the emergence of sharpshooters. Although there had been efforts to develop long-range firearms.

Before the war began, hunters in America had begun using rifled muskets that were far more accurate over greater distances. So why didn't the world's militaries upgrade if rifles existed? There were a few reasons, but one primary one.

Rifles were more expensive to produce, and ammunition had to be more uniform than musket balls, but it was also a question of practicality. A black powder smoothbore musket can take on a good amount of fouling from firing round after round and still be relatively operational.

A projectile in a rifled barrel, by necessity, must fit much tighter so it can grab the rifling on the way down the barrel. This makes reloading slower, requiring more force from the shooter.

Once fouling builds up, it not only fills in the rifling grooves making them less effective, it can also make it nearly impossible to load another projectile without cleaning the bore. This was all highly impractical for a soldier in the field at that time, and muskets were far more forgiving. In perfect conditions, a rifle could take four times as long to load as a musket.

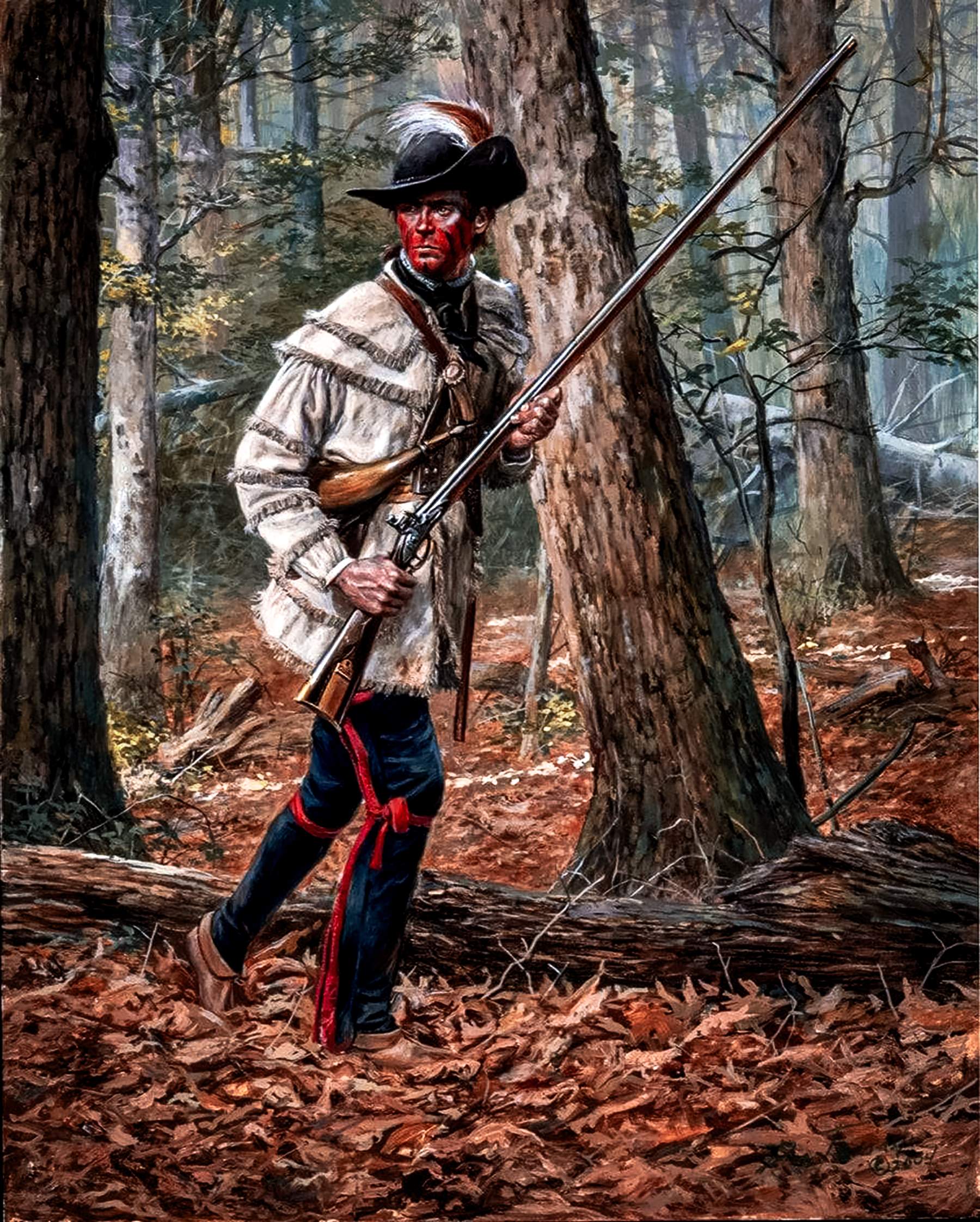

Colonial forces in the Revolutionary War employed a variety of unorthodox tactics, including dedicated sharpshooters, many of whom used their own rifled muskets. Their job was, instead of firing en masse with other soldiers, was to choose specific targets and engage them at distance and from cover. One could call them the first battlefield snipers.

General Benedict Arnold deployed riflemen at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777 to target British officers. That tactic significantly influenced the outcome of the battle, which proved critical as it convinced the French government to formally ally with the Americans.

"General Simon Fraser was killed by one of Daniel Morgan's riflemen, and the loss of a commanding officer was extremely detrimental to the organization of the British forces," explained Matthew Skic, director of collections and exhibitions at the Museum of the American Revolution.

Specialized Weapon: The American Long Rifle

The British Army was a professional fighting force with highly trained soldiers, and it was not prepared for the unorthodox warfare often employed by the Americans, including hit-and-run tactics and the use of sharpshooters.

The British "Red Coats" were also arguably "out-gunned" as the colonial forces had the unique American long rifle, aka the Pennsylvania rifle or Kentucky rifle. It was an evolution of the weapons brought by German and Swiss immigrants to the region.

Originally heavy and of substantial caliber, ranging from .45 to .60, these rifles were reduced in caliber to a more manageable .40 to .45. The weapons required less powder, were easier to carry, and less cumbersome.

Before the outbreak of the Revolution, the rifles were used primarily in the backwoods for hunting, but proved ideally suited for use by sharpshooters on the battlefield.

"'Kentucky' or 'Pennsylvania' are modern collector terms," Skic said. "[These rifles originated] in Germany in the 17th century. The rifles were introduced at the very early stages of the war. They featured a rifle bore in the barrel, but a drawback was that they took about a minute to reload."

This was due in part to its length, which could range from 5 to 6 feet and was mostly barrel.

While the rifles couldn't be reloaded as quickly as the British Army's Brown Bess or French Charleville muskets, they were far more accurate with effective ranges at ranges out to 300 yards at a time when most soldiers aimed in a general direction and hoped for the best, especially at distances greater than 50 yards.

Plus, people living on the American frontier, or darn close to it, knew how to pick their targets carefully. Before the war, they had done so to put food on the table, and they honed their skills accordingly.

The sharpshooters were likely already proficient shots when they came to the war, or they would have starved years earlier. Their impact on the battlefiend was felt in a number of ways including psychologically.

"There are numerous examples of British officers being picked off by these weapons," said Skic. "It was a great fear for some officers." So much so that some British officers modified their uniforms to make them harder to spot.

The British initially responded by deploying light infantry, who could move faster and close the distance to drive the riflemen from the battlefield, as rifles could't mount bayonets, making the men who wielded them less effective at hand-to-hand fighting.

"There was a trade-off," Skic explained. "The British adapted their tactics, with the light infantry fighting in broken terrain and woods. Washington then changed the way he used riflemen as the war went on."

That included not grouping sharpshooters together and using them more sparingly.

The First American Rifle Companies

When Congress created the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, it raised six companies of expert riflemen from the colonies of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia.

Among these was the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, also known as the 1st Continental Line and the 1st Continental Regiment, under the command of Col. William Thompson, who had come from western Pennsylvania, where he had fought Native Americans.

He was captured in June 1776, just a year later, and although he was exchanged for a British officer, he was found guilty of insulting the Continental Congress. That fact explains why his history is not well remembered today.

Better known is Col. Daniel Morgan, who led Morgan's Sharpshooters, an elite infantry unit composed of frontiersmen and skilled marksmen from Virginia and Pennsylvania.

They were noted for their brown or green hunting shirts that were more practical than a military uniform, and they operated as skirmishers, employing hit-and-run tactics. They also broke with the gentlemanly rules of the day by targeting officers.

Morgan was captured during the ill-fated invasion of Canada. After being freed, he led his riflemen in actions in New York, including Sullivan's Expedition, and later at the January 1781 Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina.

"Morgan was an extremely important officer with the Continental Army," said Skic. "His men, who came from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, were among the first non-New England troops to serve with Washington."

Washington also paid special attention to the fringed hunting shirts the men wore, noting that the clothing was suitable for all weather and made the soldiers appear to be expert sharpshooters.

The commander of the Continental Army even suggested the shirts "carry no small terror to the enemy, who thinks every such person is a complete marksman."

Targeting British Officers: The Terror of the Tories

One of the 500 handpicked men of Morgan's Riflemen was Timothy Murphy. During the Battle of Saratoga, he succeeded in shooting Brig. Gen. Simon Fraser, one of the officers leading the British forces.

Murphy scaled a tree and began firing at the general. Although his first two shots missed, the third – fired at a distance of more than 300 yards – struck the general in the stomach! Plus, he reloaded at least twice in a tree.

As Skic noted, it impacted the outcome of the battle.

After taking part in Sullivan's Expedition against the British-allied nations of the Iroquois, Murphy took part in patrols throughout New York, where he earned the reputation as "The terror of the Tories (loyalists) and Indians," while his skill with the American Long Rifle earned him the nickname "Shore Shot Tim."

Another noted Patriot was John Jacob "Rifle Jack" Peterson, who was of African and Kitchewan descent, who served with the 3rd Westchester militia.

Although Peterson isn't credited with shooting any general officers, he did fire on a British rowboat from the warship HMS Vulture on the Hudson River. His close shots forced the craft back. The next day, Petersen took part in the small battle with the larger warship.

It may have seemed entirely inconsequential at the time, but the engagement forced the Vulture to depart. However, it stranded British officer Maj. John Andre, who was arrested with evidence of Gen. Benedict Arnold's plans to surrender West Point to the British!

The British Sharpshooters

It wasn't just the Patriots who saw the effectiveness of riflemen. The British also introduced rifles to augment their light infantry units.

In addition, the Hessian troops who served with the British also carried rifles and deployed as Jägers (German for hunters). Their green uniforms distinguished them, as did their self-reliance and hunting skills; like the Colonists' riflemen, the Jägers were expert sharpshooters.

"The British and Hessians knew they could use those men in a similar marksmen role," said Skic.

There was also Patrick Ferguson, a Scottish-born British officer, who was noted for recruiting American Loyalists to serve in his militia.

Ferguson was also noted for developing a breech-loading flintlock, which allowed a user to fire up to six shots per minute: a significant advantage over contemporary muzzleloaders. He commanded an experimental unit of elite riflemen, where he proved his weapon's potential, notably at the Battle of Brandywine.

Known as "The Bulldog," he was killed during the Battle of Kings Mountain while engaging Patriot frontiersmen. However, it was noted that he made a valiant last stand and was shot multiple times while fighting to the bitter end.