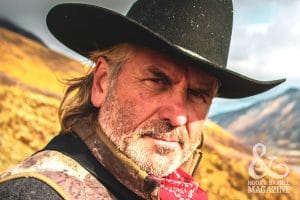

Marine combat veteran J.W. Cortés—aka Det. Carlos Alvarez on “Gotham”—walks the walk in real life with the NYPD, showing kids in the roughest neighborhoods that cops are on their side.

In 2003, platoon sergeant J.W. Cortés landed in a vast, open Kuwaiti desert, prepared for an immediate invasion of Iraq, 63 Marines in his care. As his platoon made its way to the tents, air sirens pierced the quiet. Cortés didn’t know what they meant, but he started running, leading his platoon to a makeshift bunker created by sand hills. Seeing other Marines lying down with gas masks, he did the same. Then, the Scud missiles started to rain on their position.

“At first, there was a thudding, then booms, then the earth and sand moved off the ground, taking Marines in their gas masks with them,” he says. Some were praying; Cortés was quiet, envisioning that the next impact would take his life. “I was fearful and incredibly angry. I had no way to defend myself,” he says. “I thought of the people who mattered most to me, a succession of images racing through my mind: my parents over my coffin, the kids I never had, the kid I had been who loved to act and sing and how all of that was going to die with me. Then, I had an epiphany: If I survived this earthshattering moment, I would pursue my dreams.”

For Cortés, 45, who most know as Detective Carlos Alvarez in the hit TV series Gotham, much of his early life was lived in a war zone. Born in Sunset Park Brooklyn to Puerto Rican parents, he saw the damage of PTSD first-hand from his father who had been drafted to Vietnam shortly upon his arrival in the United States. Cortés grew up in the 1980s and ’90s, in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic and in a neighborhood so violent with gangs and drugs that it was dubbed “Little Vietnam” by the cops that would show up four cars deep to answer calls.

He observed how gang leaders commanded respect on the street, flashing money, expensive cars, and influence. He saw his brother promoted to the highest ranks of the Latin Kings gang and later read about him being incarcerated for over a decade for his crimes. “My parents tried to keep me out of trouble,” Cortés says. “They told me I was destined for so much more.”

Cortés found respite in the arts. His home was filled with exuberant music—from Latin to Motown to classic rock, and his long subway ride from Sunset Park to his Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, high school became a moving stage where he and his friends would entertain riders with R&B and Doo-wop songs, basking in the applause.

At 18, fearful he would end up like his brother or dead, he enlisted in the Marines. He fell in love with the armed services and attained the rank of Gunnery Sergeant, achieving commendations, including Marine of the Year. “Everything resonated with me: the hard work, esprit de corps, teamwork, tradition,” he says. “I was desperately seeking an identity, one of respect and history.”

One of Cortés’ early assignments was to protect American embassies, including the one in Nairobi, Kenya, which he left shortly before it was bombed by Osama bin Laden in 1998, killing many of his friends.

Three years later, when he was off active duty, Cortés was confronted once again by devastation at the hand of bin Laden with the attacks on the World Trade Center as he rushed to the rubble to help rescue survivors. “I asked my commanding officer, ‘When are we going to get these guys who did this to us?’” he recalls.

He felt like he got his chance in 2002, when he was activated for Afghanistan, but to his disappointment, he did not see action. “My unit was mostly New Yorkers and FDNY and NYPD— so this was personal.” In 2003, he was routed to the invasion of Iraq, where he had his epiphany to follow his dream of performing.

Being A Cop—and Playing One on TV

Before he deployed, Cortés had considered a career in law enforcement. Upon his return from Iraq, he started the process to become a New York City police officer. “When I was a kid, I was told never to talk to cops, or people would think I was a snitch. You also did not see cops of color; they were unicorns. I was determined to be that cop who was seen and who people could see was personable, approachable, and professional.”

For most of his career, he served as a transit cop, stationed in places like Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station; currently, he is a firearm and defensive tactics instructor.

After he joined the force, Cortés began studying at the renowned William Esper Studio. At the end of his shift, he’d tuck his uniform into his locker and race from Grand Central Terminal, across midtown to get to class on time. “My instructor, Terry Knickerbocker, impressed on me that acting is a serious craft that demands respect. It’s not about celebrity; actors have a deep responsibility, providing a service because people pay good money to see them bring stories to life. He encouraged me to get curious, showed me that so much of me can be brought into the work that I don’t have to pretend to be anyone else.”

As he started auditioning, one gig led to another. He handled the inevitable rejections with the resilience he learned as a Marine. Through his career, he guest-starred in television programs, ranging from The Blacklist to the reality show Stars Earn Stripes, as well as big-screen feature and short films.

But it was his portrayal in the recurring role of Detective Alvarez in Gotham that made him a household name as the first actor to portray the iconic comic book character. “I have portrayed many detectives, but my playing Alvarez went viral because it’s not every day you see an actively serving cop playing one regularly on TV,” he says. “Gotham was a different reality. While it’s incredible to adapt my understanding of policing into a role, being Alvarez was not at all like being a real-life cop. But it was cool—it was Batman!”

Acting while policing is like juggling, in which Cortés employs a lot of skills he learned as a Marine, such as time management and discipline, and asking colleagues to switch shifts to accommodate his filming schedule. His fellow officers found his moonlighting amusing. “They would see me on shows and start calling me by my characters’ names, want to take pictures with me, and called me ‘Officer Hollywood.’” The Gotham cast showed him respect and admiration—and sometimes asked his advice or to hear his war stories.

But the rigors of patrolling took their toll. “I became angry, had difficulty sleeping and a lot of mistrust. I saw a therapist at the VA and quit drinking. I’m sober now for nine years,” he says. “Before the wave of Black Lives Matters protests took off, there already was an uptick of active duty police officers committing suicide. These protests will cause more PTSD for officers, and the pandemic adds another enemy on a plate that’s already stacked against things that can hurt cops. There is a stigma attached to those who call out for help. It’s incumbent on people like me who have dealt with PTSD to speak out and say there is hope.”

“After 9/11 there was such a level of patriotism and understanding and love toward the first responders who run into a collapsing building, who go where no one will dare go,” he continues. “It’s heartbreaking that that has lost value, that we’ve lost that respect.”

Now, Cortés pours his energy into serving as president of the Detective Rafael Ramos Foundation, which was formed in memory of a NYPD detective killed in 2014 while on duty. “When you hear a cop is killed, you think, ‘That could have been me.’ And we had a lot of similarities: We were both Puerto Rican cops with two sons,” he says.

To honor Ramos’ work in the community, the foundation’s mission seeks to ensure that the first interaction children in the most troubled, underserved neighborhoods of New York have with an officer is a positive one. Member officers organize toy drives, distribute backpacks and supplies, and spend time with the children. “They need real-life heroes,” Cortés says. “We can be that.”

He is also currently working on legislation that would create a curriculum in the state schools—and ultimately nationally—that teaches kids how to interact with police officers and understand them better.

“The life of service is in my DNA, and I will continue to give back,” he says. “I feel a sense of responsibility to do what I can because I have been afforded the gift of life while my friends are not here.”

For more information on the Detective Rafael Ramos Foundation, visit detectiverafaelramos.org.

To read more about Marines, click here.